Antigua A Short History

Antigua also known as Waladli or Wadadli by the native population, meaning land of oil, mostly likely in reference to the oil from the eucalyptus trees; is an island in the West Indies. Antigua and Barbuda is located in the Caribbean Sea, about seventeen degrees north of the equator. It is in the middle of the Leeward Islands, bordered on the north and west by St. Martin, St. Barts, St. Kitts, and Nevis, to the south by Montserrat and Guadaloupe, and to the east by the Atlantic Ocean. Antigua and Barbuda is made up of three islands: Antigua, Barbuda, and Redonda. Antigua is the largest of the three and is fourteen miles long and eleven miles wide – 108 square miles. Barbuda is thirty miles north of Antigua and is 68 square miles in area. Redonda lies to the southwest of Antigua and is only 0.6 square miles.

The island of Antigua’s lowest point is sea level and its highest point is Boggy Peak at 1,319 feet, most likely formed from volcanic activity. Barbuda is a flat coral island that houses a frigate bird sanctuary. It also has deer, guinea fowl, pigeons, and wild pigs. Both Antigua and Barbuda islands have many beaches with pink or white sand that receive protection by coral reefs. Redonda is an uninhabited rocky islet used as a nature sanctuary.

The capital and largest city of Antigua and Barbuda is St. John’s, located on the island of Antigua. Due to its existence in the Leeward Islands, the country experiences constant northeast trade winds that lessen only in September. There is low humidity year-round and an average annual rainfall of 45 inches. It can be classified as a tropical maritime climate.

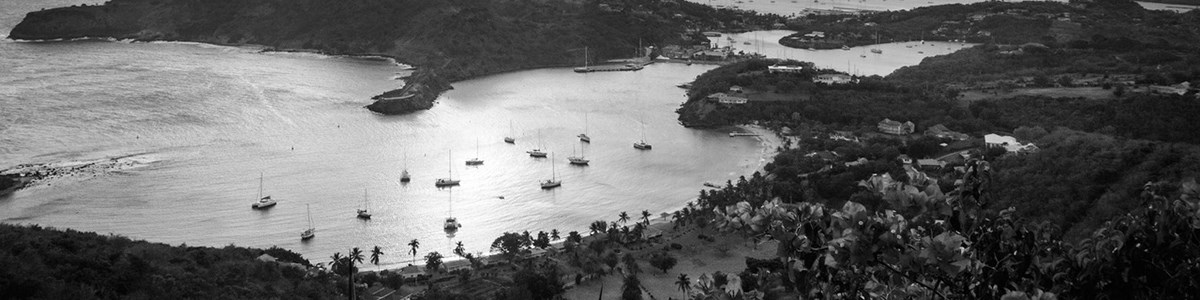

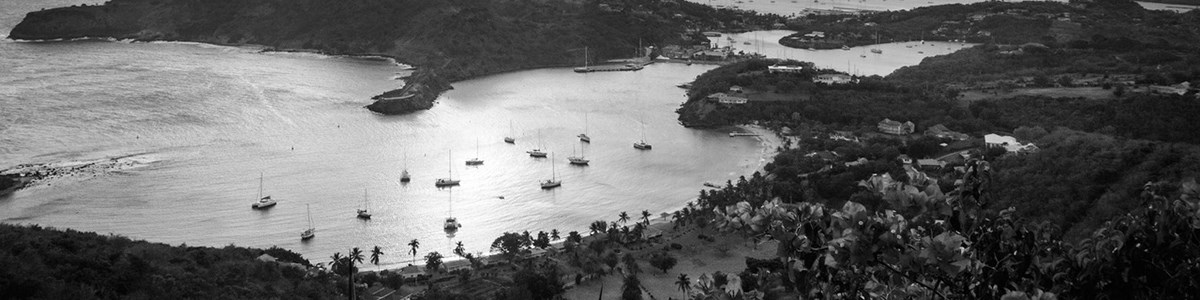

Antigua and Barbuda is an independent Commonwealth country comprising its 2 namesake islands and several smaller ones. Positioned where the Atlantic and Caribbean meet, it's known for reef-lined beaches, rainforests and resorts. Its English Harbour is a yachting hub and the site of historic Nelson's Dockyard. In the capital, St. John's, the national museum displays indigenous and colonial artefacts.

It would be difficult to overestimate the impact on Antigua's history of the arrival, one fateful day in 1684, of Sir Christopher Codrington. An enterprising man, Codrington had come to Antigua to find out if the island would support the sort of large-scale sugar cultivation that already flourished elsewhere in the Caribbean. His initial efforts proved to be quite successful, and over the next fifty years sugar cultivation on Antigua exploded. By the middle of the 18th century the island was dotted with more than 150 cane-processing windmills--each the focal point of a sizeable plantation. Today almost 100 of these picturesque stone towers remain, although they now serve as houses, bars, restaurants and shops. At Betty's Hope, Codrington's original sugar estate, visitors can see a fully-restored sugar mill.

Most Antiguans are of African lineage, descendants of slaves brought to the island centuries ago to labor in the sugarcane fields. However, Antigua's history of habitation extends as far back as two and a half millenia before Christ. The first settlements, were those of the so called Siboney (an Arawak word meaning "stone-people"), peripatetic Meso-Indians whose beautifully crafted shell and stone tools have been found at dozens of sites around the island. These pre-agricultural Amerindians known as "Archaic People" (although they are commonly, but erroneously known in Antigua as Siboney, a pre-ceramic Cuban people). The earliest settlements on the island date to 2900 BC. They were succeeded by ceramic-using agriculturalist Saladoid people who migrated up the island chain from Venezuela. They were later replaced by Arawakan speakers around 1200 AD and around 1500 by Island Caribs.

Long after the "Siboney" had moved on, Antigua was settled by the pastoral, agricultural Arawaks (35-1100 A.D.), who were then displaced by the Caribs--an aggressive people who ranged all over the Caribbean. The Arawaks were the first well-documented group of Antiguans. They paddled to the island by canoe (piragua) from Venezuela, and were ejected by the Caribs—another people indigenous to the area. Arawaks introduced agriculture to Antigua and Barbuda, raising, among other crops, the famous Antiguan "black" pineapple. They also cultivated various other foods including:

• corn

• sweet potatoes (white with firmer flesh than the bright orange "sweet potato" used in the United States)

• chiles

• guava

• tobacco

• cotton

Some of the vegetables listed, such as corn and sweet potatoes, still play an important role in Antiguan cuisine.

For example, a popular Antiguan dish, Ducuna (DOO-koo-NAH), is a sweet, steamed dumpling made from grated sweet potatoes, flour and spices. In addition, one of the Antiguan staple foods, fungee (FOON-ji), is a cooked paste made of cornmeal and water.

The bulk of the Arawaks left Antigua about 1100 AD. Those who remained were subsequently raided by the Caribs. According to the Catholic Encyclopedia, the Caribs' superior weapons and seafaring prowess allowed them to defeat most Arawak nations in the West Indies—enslaving some and cannibalising others.

The Catholic Encyclopedia does make it clear that the Spanish explorers had some difficulty identifying and differentiating between the various native peoples they encountered. As a result, the number and types of ethnic-tribal-national groups in existence at the time may be much more varied and numerous than the two mentioned.

The earliest European contact with the island was made by Christopher Columbus during his second Caribbean voyage (1493), who sighted the island in passing and named it after Santa Maria la Antigua, the miracle-working saint of Seville. European settlement, however, didn't occur for over a century, largely because of Antigua's dearth of fresh water and abundance of determined Carib resistance. Finally, in 1632, a group of Englishmen from St. Kitts established a successful settlement, and in 1684, with Codrington's arrival, the island entered the sugar era.

By the end of the eighteenth century Antigua had become an important strategic port as well as a valuable commercial colony. Known as the "gateway to the Caribbean," it was situated in a position that offered control over the major sailing routes to and from the region's rich island colonies. Most of the island's historical sites, from its many ruined fortifications to the impeccably-restored architecture of English Harbourtown, are reminders of colonial efforts to ensure its safety from invasion.

Horatio Nelson arrived in 1784 at the head of the Squadron of the Leeward Islands to develop the British naval facilities at English Harbour and to enforce stringent commercial shipping laws. The first of these two tasks resulted in construction of Nelson's Dockyard, one of Antigua's finest physical assets; the second resulted in a rather hostile attitude toward the young captain. Nelson spent almost all of his time in the cramped quarters of his ship, declaring the island to be a "vile place" and a "dreadful hole." Serving under Nelson at the time was the future King William IV, for whom the altogether more pleasant accommodation of Clarence House was built.

It was during William's reign, in 1834, that Britain abolished slavery in the empire. Alone among the British Caribbean colonies, Antigua instituted immediate full emancipation rather than a four-year 'apprenticeship,' or waiting period; today, Antigua's Carnival festivities commemorate the earliest abolition of slavery in the British Caribbean.

Emancipation actually improved the island's economy, but the sugar industry of the British islands was already beginning to wane. Until the development of tourism in the past few decades, Antiguans struggled for prosperity. The rise of a strong labour movement in the 1940s, under the leadership of V.C. Bird, provided the impetus for independence. In 1967, with Barbuda and the tiny island of Redonda as dependencies, Antigua became an associated state of the Commonwealth, and in 1981 it achieved full independent status. Lester B. Bird, was elected to succeed his father V.C. Bird as prime minister.

According to A Brief History of the Caribbean (Jan Rogozinski, Penguin Putnam, Inc September 2000), European and African diseases, malnutrition and slavery eventually destroyed the vast majority of the Caribbean's native population. No researcher has conclusively proven any of these causes as the real reason for the destruction of West Indian natives. Some historians believe that the psychological stress of slavery may also have played a part in the massive number of native deaths while in servitude. Others believe that the reportedly abundant, but starchy, low-protein diet may have contributed to severe malnutrition of the "Indians" who were used to a diet fortified with protein from sea-life.

The Indigenous West Indians made sea vessels that they used to sail the Atlantic and Caribbean. As a result, Caribs and Arawaks populated much of South American and the Caribbean Islands. Relatives of the Antiguan Arawaks and Caribs still live in various countries in South America, notably Brazil, Venezuela and Colombia. The smaller remaining native populations in the West Indies maintain a pride in their heritage.

European Colonization (1632–1981)

Antigua was colonized by English settlers in 1632 and remained a British possession although it was raided by the French in 1666. The early colonizers were also attacked by Caribs, who were once one of the dominant peoples of the West Indies. At first tobacco was grown, but in the later 17th century sugar was found to be more profitable.

The nearby island of Barbuda was colonized in 1678. The crown granted the island to the Codrington family in 1685. It was planned as a slave-breeding colony but never became one; the slaves who were imported came to live self-reliantly in their own community.

The emancipation in 1834 of slaves, who had been employed on the profitable sugar estates, gave rise to difficulties in obtaining labour. An earthquake in 1843 and a hurricane in 1847 caused further economic problems. Barbuda reverted back to the crown in the late 19th century, and its administration came to be so closely related to that of Antigua that it eventually became a dependency of that island.

The Leeward Islands colony, of which the islands were a part, was defederated in 1956, and in 1958 Antigua joined the West Indies Federation. When the federation was dissolved in 1962, Antigua persevered with discussions of alternative forms of federation. Provision was made in the West Indies Act of 1967 for Antigua to assume a status of association with the United Kingdom on February 27, 1967. As an associated state, Antigua was fully self-governing in all internal affairs, while the United Kingdom retained responsibility for external affairs and defense.

By the 1970s Antigua had developed an independence movement, particularly under its prime minister George Walter, who wanted complete independence for the islands and opposed the British plan of independence within a federation of islands. Walter lost the 1976 legislative elections to Vere Bird, who favoured regional integration. In 1978 Antigua reversed its position and announced it wanted independence. The autonomy talks were complicated by the fact that Barbuda, long a dependency of Antigua, felt that it had been economically stifled by the larger island and wanted to secede. Finally, on November 1, 1981, Antigua and Barbuda achieved independence, with Vere Bird as the first prime minister. The state obtained United Nations and Commonwealth membership and joined the Organization of Eastern Caribbean States. Bird’s Antigua Labour Party (ALP) won again in 1984 and 1989 by overwhelming margins, giving the prime minister firm control of the islands’ government.

The postindependence political landscape of Antigua and Barbuda remained relatively stable, although the government was the subject of intermittent scandals and corruption allegations. Bird retained office until his retirement in 1994, after which his son, Lester, served as prime minister from 1994 to 2004. He was succeeded by Baldwin Spencer of the United Progressive Party, who also spent a decade in office. In 2009 the economy suffered after one of the country’s largest investors, U.S. financier Robert Allen Stanford, was arrested and charged with fraud; in 2012 a Texas court found him guilty of having run a Ponzi scheme from his offshore bank on Antigua. In the June 2014 legislative elections the ALP regained power under Gaston Browne. Browne and the ALP then retained power in early elections held in March 2018.

The islands achieved independence from the United Kingdom in 1981, becoming the nation of Antigua and Barbuda. However, it remains part of the Commonwealth of Nations, and remains a constitutional monarchy, with Queen Elizabeth II as Queen of Antigua and Barbuda.

The median age is about 30 years.

The life expectancy at birth is 84 years.

The Eastern Caribbean dollar is used in Antigua and Barbuda. It is represented by the $ and the code XCD or EC$. It is similar to the United States dollar in coin denominations. The $1 is used in the form of a coin and not as paper money. There are bank notes for 5, 10, 20, 50, and 100 dollars. The exchange rate has been fixed since 1976 with the U.S. dollar at US$1 = EC$2.7.

The literacy rate in Antigua and Barbuda is over 90%. There is a governmentowned state college and several other colleges and universities, along with some international schools. A national mandate was established in 1998 to make Antigua and Barbuda the best provider of medical services in the Caribbean. There are now two medical schools, the American University of Antigua (AUA) and The University of Health Sciences Antigua (UHSA).

English is the official language. There are some local dialects, the major one being Antiguan Creole. This dialect mixes its British and African origins. Some Spanish is spoken in the areas that have high immigration from the Dominican Republic. There is no religious persecution and religion is a freedom guaranteed in the Constitution.

Agriculture only makes up 3.8% of the GDP. This is because of the limited freshwater supply and most of the labor force being drawn to tourism. Most of the agricultural production is for domestic consumption. Some crops produced are cotton, bananas, coconuts, cucumbers, mangoes, and sugarcane. There is some livestock production. Trade Antigua and Barbuda export petroleum products, bedding, handicrafts, electronic components, transport equipment, food, and live animals. It imports food, live animals, machinery, transport equipment, manufactures, chemicals, and oil.

The tourism industry has prompted many restaurants to open and offer more of an international cuisine.

There are several interesting locations to visit while in Antigua and Barbuda. English Harbor has a great history of being a leader in the maritime enterprises of the British. Nelson’s Dockyard, named after Horatio Nelson, has been restored and is the only Georgian dockyard in the world. Nearby English Harbor is Shirley Heights, an old military lookout point. Sea View Farm Village offers a chance to revisit the early 18th century and the folk pottery made by slaves. There is Harmony Hall Art Gallery and the Museum of Antigua and Barbuda to visit as well.

Much of the culture of Antigua and Barbuda is British and the sports are no exception. The national sport is Cricket and it is very prevalent. The 2007 World Cricket Cup was played in the West Indies and eight matches were held at Sir Vivian Richards Stadium in St. John’s. Soccer (called football on the islands) is another common sport. Athleticism is accepted overall and many famous athletes have come from or represented Antigua and Barbuda. On the Olympic stage, most compete in the track and field events. Sailing, diving, and other water sports are popular too.